In my last post, I gave an introduction into a couple aspects of testosterone: how it rises and falls, and how it affects decision-making. I forgot to mention that, neurally, it appears to act substantially through three areas of the brain: the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). The nucleus accumbens is a major dopaminergic center, the molecule generally seen as responsible for decision-making and action selection. Amygdala, as we all know, mediates fear and emotional responses (generally…). The more interesting area is OFC, which is typically thought to be an area that is involved in self-control. I couldn’t find many papers that I really wanted to talk about on this aspect of testosterone, so I’ll wait for another day to delve into it.

So let’s look at how testosterone affects social behavior. In what must have been the Most Fun Study To Participate In Ever, Oxford et al. asked subjects to play Unreal Tournament in teams. When men are playing the game against other teams, the players that contribute the most show increases in testosterone. However, when men are forced to play against their own teammates, they have decreased testosterone! And the subjects who contributed the most to a win showed the largest change.

But if testosterone is increasing during competition against other groups, what affect might it have on social behavior? Eisenegger et al. used the ultimatum game, where a pair of subjects are given a small amount of money. One of the subjects then makes an offer of part of the money to the other subject, who can either accept the money or reject it; when the second subject rejects it, neither subject gets any money. It is well-known that people will generally reject unfair offers. Following the framework of past studies, female subjects were given either testosterone or placebo and asked to play the game. They found that subjects who were given testosterone made larger offers than placebo subjects. Although the authors try to make the claim that this is because being turned down is a ‘status concern’, it could just be because they think that they will make more money that way? Maybe this is risk-aversion? I should also note that different study found that subjects given testosterone and asked to be the second subject will also reject more unfair offers. But the most interesting part about the study is that the subjects who thought that they had received testosterone made much smaller offers – presumably because they already thought they knew what testosterone should do, even though they were wrong!

In a response, van Honk et al. tried using a different game. He used the ‘public good game’ which is where all players receive 3 moneys, and can contribute some to the public good. When at least two players contribute to the public good, all players receive 6 moneys. Note that in this version of the game, with the contribution rate of other players, the expected value is highest when you contribute to the public good. And subject who have testosterone administered to them give more often to the public good! So it’s not clear whether they are being more pro-social or just smarter…

In a response, van Honk et al. tried using a different game. He used the ‘public good game’ which is where all players receive 3 moneys, and can contribute some to the public good. When at least two players contribute to the public good, all players receive 6 moneys. Note that in this version of the game, with the contribution rate of other players, the expected value is highest when you contribute to the public good. And subject who have testosterone administered to them give more often to the public good! So it’s not clear whether they are being more pro-social or just smarter…

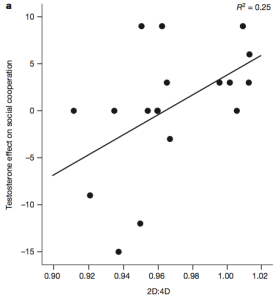

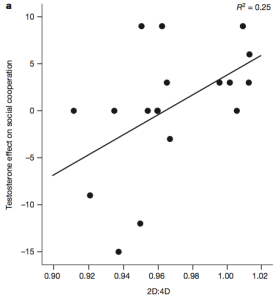

The interesting thing about this paper, though is that they also measured the ratio of ring to index finger. This is a measure of prenatal testosterone exposure, although it doesn’t predict adult levels of testosterone. Those with a high 2D:4D ratio (ie, those  with low maternal testosterone, figure left) are most likely to contribute to the common good, and the less prenatal testosterone, the more of an effect the testosterone given to subjects has. van Honk et al. suggest that prenatal exposure may change something physically to make subjects more receptive to testosterone, whether it is metabolism or receptor level. They had found a similar result in a previous study which showed that suspicious individuals didn’t become any more suspicious from testosterone, but the most trusting individuals became much more suspicious when given testosterone (figure right).

with low maternal testosterone, figure left) are most likely to contribute to the common good, and the less prenatal testosterone, the more of an effect the testosterone given to subjects has. van Honk et al. suggest that prenatal exposure may change something physically to make subjects more receptive to testosterone, whether it is metabolism or receptor level. They had found a similar result in a previous study which showed that suspicious individuals didn’t become any more suspicious from testosterone, but the most trusting individuals became much more suspicious when given testosterone (figure right).

The data is a bit hard to interpret, but the general feeling now is that testosterone can act as either a pro-social hormone, or one that makes you more concerned about your social status (egocentrism?). Although I’d love to give a good clean explanation here, I cannot come up with – and have not yet found – a good unifying framework that unites all the social effects of testosterone .

References

Eisenegger, C., Naef, M., Snozzi, R., Heinrichs, M., & Fehr, E. (2010). Prejudice and truth about the effect of testosterone on human bargaining behaviour Nature, 463 (7279), 356-359 DOI: 10.1038/nature08711

van Honk, J., Montoya, E., Bos, P., van Vugt, M., & Terburg, D. (2012). New evidence on testosterone and cooperation Nature, 485 (7399) DOI: 10.1038/nature11136

Oxford, J., Ponzi, D., & Geary, D. (2010). Hormonal responses differ when playing violent video games against an ingroup and outgroup Evolution and Human Behavior, 31 (3), 201-209 DOI: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.07.002

When studying decision-making in neuroscience, experimenters like to have participants be rewarded with money – or units of juice or ‘points’ or suchlike. Although this may seem like a natural way to measure decisions, we have to step back and ask ourselves whether using this as a basis for reward will affects decision-making in anyway. Looking around, I found a recent review paper by Bowles and Polania-Reyes that examined how explicit economic incentives change motivation. Even though it is meant for economists, it has good things to think about for everyone interested in decision-making, motivation, and interpersonal behavior.

When studying decision-making in neuroscience, experimenters like to have participants be rewarded with money – or units of juice or ‘points’ or suchlike. Although this may seem like a natural way to measure decisions, we have to step back and ask ourselves whether using this as a basis for reward will affects decision-making in anyway. Looking around, I found a recent review paper by Bowles and Polania-Reyes that examined how explicit economic incentives change motivation. Even though it is meant for economists, it has good things to think about for everyone interested in decision-making, motivation, and interpersonal behavior.